Editor’s Note: Russ Whitehurst delivered the following testimony on early childhood education to the Committee on Education and the Workforce of the U.S. House of Representatives on February 5, 2014.

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee,

I’m pleased to testify before you. My name is Russ Whitehurst. I am director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution, where I am a senior fellow and hold the Herman and George R. Brown Chair in Education Studies.

Today I wear my hat as a Brookings policy expert and as an expert on research methodology, the latter reflecting my role as the founding director of the Institute of Education Sciences within the U.S. Department of Education.

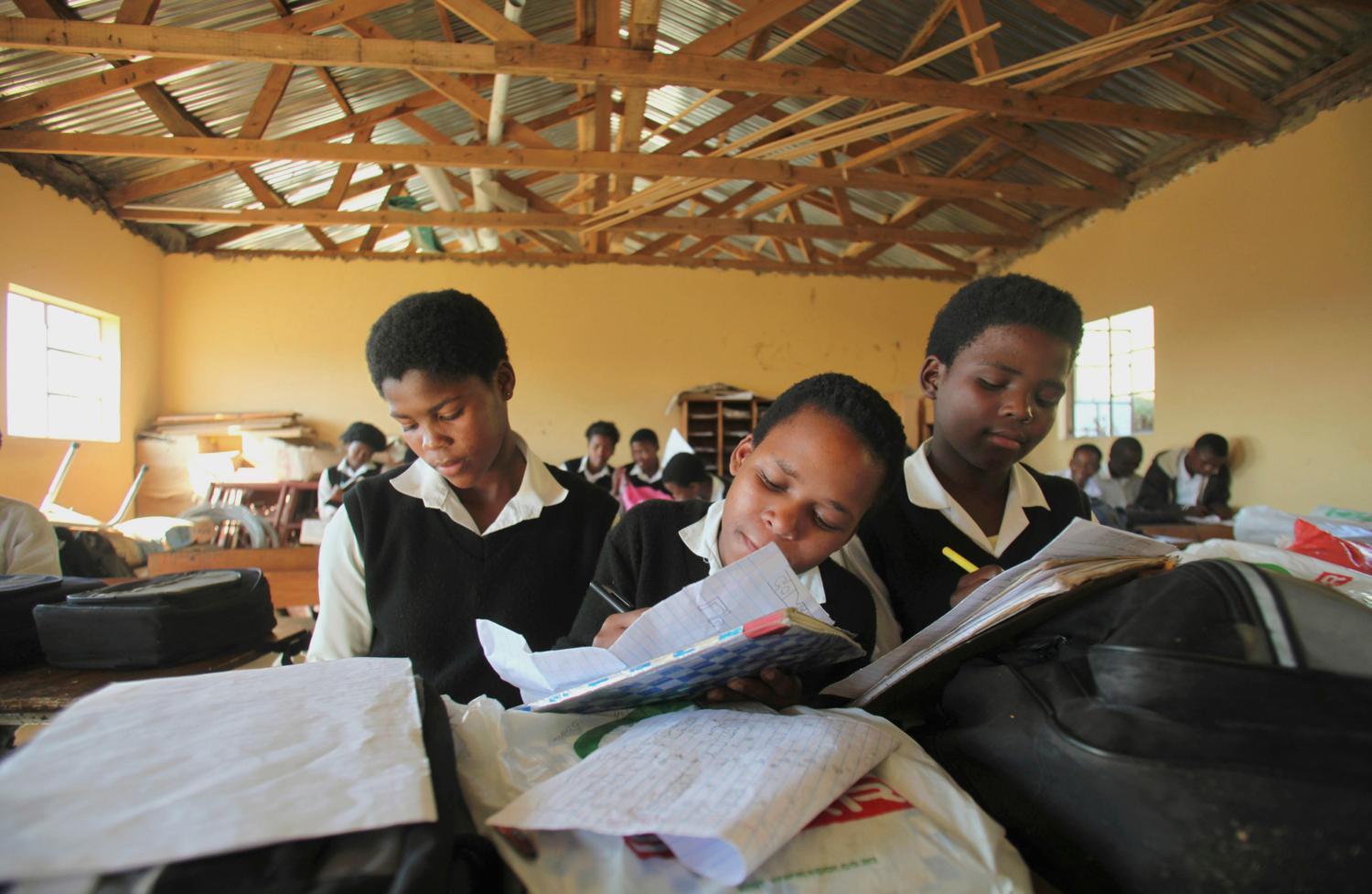

But I also bring to my testimony my long experience in my first career as a developmental psychologist conducting research on programs to enhance the language and cognitive development of young children. I’ve spent a lot of time in childcare facilities that were under the sway of federal legislation, including Head Start, Even Start, and subsidized daycare centers. I observed classrooms that I would have been pleased to have my own children attend, but I also saw far too many situations that made me want to cry. I also saw over and over again families that wanted to do what was right for their children and needed something better than what they were getting.

I remember vividly a young mother I met at a parents meeting at a Head Start center at which I was doing research. When I was later leaving the center in my car I saw her walking down the road at twilight with her 4-year-old in hand, pushing her 2-year-old in a stroller, and carrying a large bag of materials that had been passed out at the meeting. She was struggling. I asked her if she wanted a ride home. She accepted. I thought I would be taking her a few blocks but it was a couple of miles before we pulled up in front of the dilapidated home where she lived. I asked if she had walked all the way to the meeting. She had. I asked if she had known how far it was. She had. I said, “That’s a long way to walk with two young children. Why did you do it?” Her answer – “I just want to do what’s best for my babies.”

We all should want a system of funding that would allow her and millions of parents like her to do just that – what’s best for their babies. In that regard, the federal government has for nearly 100 years recognized a responsibility for supporting the education of the disadvantaged, with that role strengthened and clarified in the last 50 years. Children learn in and are affected by childcare settings as surely as they learn in and are affected by public schools. Many young children who are vulnerable and at-risk of later difficulties in school and life need the boost that they can derive from high quality care outside the home. Their parents need safe and supportive childcare for their children in order to find and hold work, and in order to increase their own skills and employability. When the nation does not attend to these needs, society as a whole suffers the consequences.

The question for me is not whether the federal government should support the learning and care of young children from economically disadvantaged homes and otherwise vulnerable status but how it should do so. The current system, a mishmash of 45 separate, incoherent, and largely ineffective programs, fails to serve the broader public and certainly is less than optimal for the children and families to which it is directed.

My goal today is to offer some policy recommendations that are within the realm of political reality and would reform present federal efforts, that are grounded in a hard-headed examination of what we know and don’t know about effective early childhood programs and child development, and that are motivated by the desire to improve the prospects of the most vulnerable among us.

Things we know (or should know)

1) The federal government spends disproportionately on early childhood programs relative to its expenditures at other levels of learning.

According to the GAO, there are 12 federal programs that are explicitly focused on early learning and childcare for children under five years of age, accounting for annual federal expenditures of around $14 billion. Head Start and the Child Care Development Block Grant program are the largest. My colleague at Brookings, Ron Haskins, who for many years was a staff member of the Committee on Ways and Means, uses a broader definition of federal early childhood programs than the GAO and pegs annual federal expenditure at over $22 billion.[i] By way of comparison, the federal government’s entire expenditure on the education of the disadvantaged in grades K-12 under Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which serves children from ages 5 through 18, is roughly $15 billion.

My point is this: I’m not sure how much the U.S. taxpayer ought to be spending on early learning and childcare, but relative to other federal expenditures on education we’re spending a healthy amount.

My back-of-the envelope calculation using $20 billion as a rough and ready estimate of federal expenditure and the National Center for Children in Poverty estimates of children living in poverty [ii] is that we are spending $5,000 a year in federal dollars for early childhood programs for every child in poverty in the U.S. under 5 years of age. And since the uptake of childcare services is not universal and skews heavily towards older preschoolers, the expenditure level per child actually served is much higher. If we take present uptake rates into account and again assume $20 billion in annual federal expenditure, we are spending roughly $10,000 per child per year on early learning and childcare for every child in poverty below school age in America. This doesn’t take into account state spending, which according to the same Haskins analysis adds another $8 billion or so in annual expenditure. To this the Obama administration proposes adding another $15 billion a year in federal and state expenditures for Preschool for All.

Billions here, billions there — we’re talking real money.

I don’t think the problems we have with early childhood programs in this country are about underfunding, at least not at the federal level.

2) We are not getting our money’s worth from present federal expenditures on early childhood services.

If the point of federal expenditures is that vulnerable children will learn transformative skills and dispositions from early center-based care that will eliminate the gaps in school readiness between them and more advantaged children, and enable them to get more out of every additional investment in their education, we are almost surely not getting our money’s worth from current programs, much less the rich returns on investment that are touted by advocates for universal pre-K.

Head Start. The largest single federal investment in the early education of disadvantaged children, Head Start, produces no lasting educational gains for participants. It doesn’t even produce gains that last until the end of kindergarten. We know this from the Head Start Impact Study, a recent federal evaluation involving a nationally representative sample of over-subscribed Head Start centers. Children winning and losing lotteries for admission to these centers have been followed through 3rd grade. In the words of the authors of the most recent report, “by the end of 3rd grade there were very few impacts … in any of the four domains of cognitive, social-emotional, health and parenting practices. The few impacts that were found did not show a clear pattern of favorable or unfavorable impacts for children.”

Those are the results of the evaluation of Head Start that Congress authorized and funded – children who have the opportunity to attend Head Start do no better in school than equivalent children who do not have that opportunity. The budget for Head Start was increased to $8.6 billion under the 2014 Omnibus Appropriations Act, $612 million more than the 2013 enacted level.

CCDBG. Expenditures for childcare under the Child Care Development Block Grant Program and the Child Care Development Fund may actually do harm to some children because various aspects of how the CCDBG programs are administered at the state level lead families to place their children in low-quality facilities that provide a less secure and stimulating environment than the children could receive at home. [iii] Examples of design flaws include low reimbursement rates, co-pays for families based on a percentage of tuition that encourage shopping for the cheapest provider, brief and uncertain periods of eligibility for parents that lead to instability in children’s placements, and pervasive lack of information to families to support choice of high quality providers.

Other federal programs. Other recent federal programs intended to enhance early learning are no more effective than Head Start. The Even Start program, a Head Start-like program that was designed to improve the literacy and work skills of parents along with the development of their preschoolers was finally defunded a few years ago after three national evaluations found no impact of program participation on either children or parents. The Early Reading First program is no longer with us. Its national evaluation found only a small impact on one outcome at the end of the pre-K year. The federal Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Project examined the impact of 14 pre-K curricula in separate randomized trials. Only one had impacts in the pre-K year that lasted through the end of kindergarten. Ten had no effects at either the end of pre-K or kindergarten on any of 12 student outcomes that were measured.

3) State programs may be no more effective than Head Start.

Do we find more evidence of program success when we look to state pre-K programs, the kind of programs the Obama administration wishes to expand dramatically under Preschool for All? Not really.

The research on these programs that is touted by advocates of universal pre-K has serious flaws. Important among them is that the research design that has been used in studies in Tulsa, New Jersey, and Boston is only capable of detecting differences between participants and non-participants at the end of the pre-K year.[iv] No long-term follow-up is possible. That is because the studies compare children who are just starting pre-K with those who have just finished pre-K, a delayed treatment research design in which the control group also gets pre-K services, just a year later than the treatment group. At that point there is no longer a control group. But research shows clearly that some pre-K programs, including Head Start, can impact children’s learning when measured when children are just finishing the pre-K year. The whole issue is about whether the pre-K experience produces a lasting advantage. If a research design can’t answer that question, and the Tulsa-type research studies cannot, the findings aren’t relevant to decisions that pivot on estimates of the return on investment in early learning and childcare.

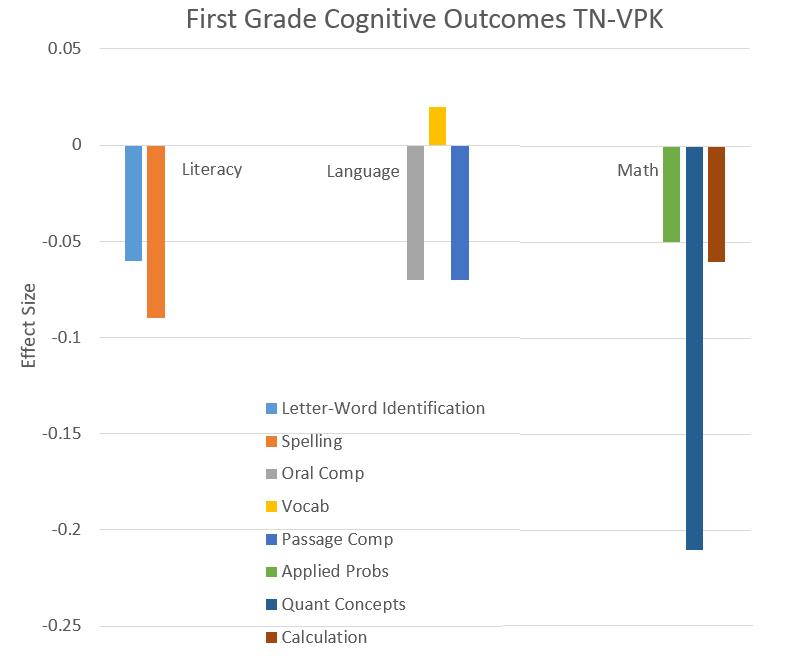

The strongest piece of research on the impact of state pre-K programs is the recently reported findings from an evaluation of Tennessee’s Voluntary Pre-K Program (TN-VPK). TN‐VPK is a full day pre-k program for four‐year‐olds from low-income families. It has quality standards that are high and in keeping with those proposed by the Obama administration under Preschool for All, including the requirement of a licensed teacher in each classroom, no more than 10 children per adult, and an approved and appropriate curriculum. The study was conducted as randomized trial (the gold standard for evaluating program impacts) using a lottery to select participants from those who were seeking admission to oversubscribed programs. Only about a quarter of children in the control group found their way into other center-based programs such as Head Start or private pre-k, so the study compares groups that are very different in their levels of access to early childhood education.

The figure below illustrates the impact of TN-VPK participation on cognitive abilities at the end of first grade (kindergarten findings are very similar). Bars above zero favor the treatment group. Those below zero represent outcomes that favor the control group. As the figure shows, seven of the outcomes favor the control group, with one (quantitative concepts) being statistically significant. In other words, the group that experienced the Tennessee Voluntary State Pre-K Program performed less well on cognitive tasks at the end of first grade than the control group, even though ¾ of the children in the control group had no experience as four-year-olds in a center-based early childhood program of any sort. Similar results were obtained on measures of social/emotional skills. Further, children in the pre-K treatment group were receiving special education services at higher rates than children in the control group.

All other existing research on state pre-K programs is methodologically weaker than the TN-VPR study, but it points in a similar direction. There are, for example, two credible attempts to estimate the state-wide impact of the universal pre-K programs that are touted by the Obama administration and other advocates as models for the nation – one study is of the Georgia program;[v] the other examines Georgia and Oklahoma.[vi] Both studies use student scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress as the outcome, comparing growth rates on NAEP in the target states with growth rates in states without state funded pre-K. The impacts on student achievement are, at best, very small. The author of the study of Georgia concludes that the Georgia universal pre-K program has costs that exceed its benefits.

4) The results from Perry and Abecedarian cannot be generalized to present-day programs.

Who among us has not heard the claim that a dollar invested in quality preschool returns $7 in public benefits (or perhaps $13 or $18, depending on the source)?

These estimates are derived from two studies of small pre-K programs in Chapel Hill, NC (the Abecedarian program) and Ypsilanti, MI (the Perry program). The studies were conducted as randomized trials and the participants and control group members have been followed into adulthood. The findings as reported favor the participants.

But while the research design of these studies was a gold-standard randomized trial and the results are favorable for participants, these programs were implemented many decades ago, and the nature of what they delivered is very different from current state and federal programs. In particular, they were small hothouse programs with only about 50 program participants each. They were multi-year intensive interventions involving family components as well as center-based childcare. Costs per participant were multiples of the levels of investment in present-day programs, e.g., $90,000 per child for Abecedarian. They were run by very experienced, committed teams. The circumstances of the very poor families of the Black children who were served by these model programs were very different from those faced by the families that are presently served by publicly funded preschool programs. For example, nearly half of the four-year-olds in Head Start today are Hispanics, whereas there were no Hispanic children in Abecedarian or Perry. And 40 years ago other government supports for low-income families were at much lower levels, pre-K was not widely available for anyone, much less the poor, and even kindergarten was rare.

Thus, even without the recent findings from Head Start and the TN-VPK there would be reason to be skeptical that widely deployed state and federal preschool programs could produce the return of investment that has been attributed to Perry and Abecedarian. But even the findings from the studies of Perry and Abecedarian are in doubt because the researchers collected data on several hundred outcomes and did not adjust for the likelihood that 5% of those outcomes would appear to be statistically significant simply on the basis of chance. When the data are properly analyzed most of the differences disappear.[vii] So when you hear that every dollar invested in quality pre-K today will return $7 or more tomorrow, swallow with a grain of salt, or not at all. Perry and Abecedarian are slender reeds on which to base billions of dollars of federal expenditure.

5) Only some children need pre-K services to be ready for school and life.

The normal development of children is well-buffered against a reasonably wide range of environmental circumstances. Most young children do not need to experience organized center-based care in order develop normally, profit from later educational opportunities, and live happy and productive lives.

So far as my staff has been able to determine by reading published biographies, none of the 44 presidents of the United States attended a pre-K or nursery school program. I’m sure many people in this room did not have pre-K. This is not to say that children can’t derive some benefit from being in organized pre-K setting. And who can say that presidents Obama, Bush, Clinton, and Carter wouldn’t have been better presidents if only they had gone to preschool. But somehow we’ve gotten to the point as a society of thinking that pre-K is essential to normal child development and should be universal. That’s bunk.

Some children are reared in circumstances that are pathogenic, i.e., they cause lasting damage to the child – think of a two-year-old being raised by a drug-addicted single mother. The child spends most of her waking hours in a crib, is malnourished, and hears no more than a few utterances from her mother in a week, all of which are short directives such as “be quiet” and “don’t spill your food.” Such children will profit enormously from spending their waking hours in good out-of-home care.

Some childcare settings are also pathogenic. Think of a childcare center that is dirty, serves 20 children per adult, has such high staff turnover that there is no continuity in adult-child relationships (except for the children who are in the care of the adults who yell, abuse, and tend to stick around), and has no curriculum other than custody. Children in such centers will profit enormously from not being there.

Many children, particularly those from low-income and immigrant backgrounds, are reared in environments that don’t adequately support the development of the skills and dispositions the children are expected to have when they start formal schooling. Think of a child whose parents don’t speak English, have low literacy levels in their native language, and don’t know that their child would profit from opportunities to learn such as those that are provided by shared picture book reading at home. These children will benefit from effective interventions to help their parents provide them a more supportive environment at home and from good pre-K programs in which they can acquire English, broader knowledge of the world, and simple skills such as alphabet knowledge.

In contrast, some children are reared in families in which they have lots of opportunities to interact with the loving adults in their lives in ways that support cognitive and socio-emotional growth. Many such children will be better off at home than in a preschool classroom in which they are one of 18 children and the adults feel overworked and underpaid.

Consistent with these points, every credible evaluation of early childhood education interventions of which I’m aware shows that the impacts, when they are found at all, are concentrated at the lower end of the distribution of family socio-economic status and in families in which the parents don’t speak English at home.

6) The impact on children of differences in quality of the childcare staff and teachers with whom they interact will be much larger than the impact of differences in the quality of the centers they attend. Neither formal credentials nor the extent of professional development are meaningfully associated with these differences in teacher quality.

Many of the policy proposals bouncing around that are intended to improve the quality of early childhood center-based services through law and regulation are based on models that have been thoroughly discredited in research on K-12 education. These discredited models place an emphasis on inputs such as the credentials of teachers, their pay, expenditures on professional development, and regulatory systems that focus on the center as unit of evaluation and accountability. But we know primarily from research in K-12, with some supporting research in pre-K settings, that teacher credentials and teacher professional development bear scant if any relationship to teacher effectiveness, that levels of expenditure beyond a certain point are only weakly related to student learning, and that the teacher to which a child is assigned is far more important that the aggregate quality of the school the child attends.

K-12 teacher policy at the federal level has transitioned from a focus on teacher quality as measured by credentials to teacher quality as measured by on-the-job performance in the classroom, with a growing realization that the most powerful management tools that affect student outcomes of which educators and policymakers can avail themselves are in the area of teacher retention. In short, policies that have the effect of keeping good teachers in the classroom and encouraging bad ones to leave are one of the few sure ways of improving student outcomes. None of this seems to have penetrated policy thinking in early childhood.

7) Early childhood programs have important functions for parents and the economy, independent of their impacts on children. We ought not to focus exclusively on early learning as the yardstick for measuring the value of public expenditures on childcare.

Federal support for childcare for poor families, if designed and implemented properly, enables parents to work, live productive lives, and raise their children adequately. For example, even with the serious flaws in the CCDBG as childcare program, research demonstrates that childcare subsidies under the CCDBG increase employment, reduce welfare, and allow recipients to invest in their human capital by enrolling in job training or taking college level courses.[viii] Further, we cannot reasonably require parents of young children to work if they do not have the resources to purchase childcare. Continued federal investment in early childcare is essential for these reasons without recourse to the rationale that early childcare narrows achievement gaps and produce lifelong benefits for participants.

A policy proposal

Goals and assumptions

There is no compelling reason that flows from the long-term well being of children for the federal government to expend resources on universal pre-K programs such as proposed under the Obama Administration’s Preschool for All. Existing research demonstrates that middle-class parents receive a disproportionate financial benefit from universal programs because they shift their preschoolers from care they paid for themselves to care that is paid for by the taxpayer.[ix] If the goal of federal or state programs is to create access and increase participation, covering the childcare expenses of middle class families does neither. Federal expenditures should be targeted on families that cannot otherwise afford childcare.

The most vulnerable children raised in the most pathogenic family circumstances should have access to programs that help their parents and improve their circumstances beginning at or prior to their birth. Programs for 4-year-olds and even 3-year-olds come too late.

The CCDBG program should be reformed so that the funding stream is part of a reliable and predictable source of support for out-of-family childcare for low-income working parents and so that it provides parents with useful information about their choices of childcare.

Head Start should be sunset, with the funds redirected to the same purpose as the CCDBG program – a reliable and predictable source of support for out-of-family childcare for low-income working parents.

States have a critical role to play as partners of the federal government’s support of childcare in three areas: establishing licensing and oversight processes that rid the childcare market of pathogenic service providers, collecting information on the quality and effectiveness of center-based childcare providers and assuring that parents avail themselves of it, and incentivizing center-based providers to engage in consequential evaluation of the on-the-job performance of their childcare staff.

We know far less than the advocacy community and many members of research community would have you believe about who needs what early childhood services when. We should be modest about the state of current knowledge. Accordingly, the design philosophy around Congressional efforts should be to create childcare systems that can evolve and learn based on feedback from their customers and users, rather than to mandate the characteristics such systems should have in order to be of high quality.

If redesigned to be coherent and focused on low-income families, current levels of federal expenditure are adequate as a starting point for an effective system of support for childcare.

The Early Learning Family grant (ELF)

One way that my policy recommendations could be translated into legislation would be through the creation of a federal grant program for early childcare – The Early Learning Family (ELF) grant – that is conceptualized along the lines of the federal Pell grant system, which supports the college tuition costs of low-income students. Like Pell grants go to students, ELF grants would go to parents in the form of a means-tested voucher that the family carries with them to the state-licensed childcare provider of their choice. That is very different from the present system in which federal dollars flow directly to Head Start and to states. ELF grants would replace most present forms of federal financial aid for early learning and childcare, including Head Start and CCDBG, and would place families in the driver’s seat instead of federal and state bureaucracies. I provide additional details on ELF in the appendix.

Conclusion

Congress has a choice. It can continue to tinker with current programs and create new programs under Preschool for All for which states have to jump through hoops that are designed in Washington and that will change in ways that have little to do with program effectiveness as the political winds blow from other directions. Or it can place the financial resources to purchase early learning and care directly in the hands of families it is intended to serve, as it does with expenditures to support college attendance.

I’m confident that a system in which federal dollars follow children to the childcare service of their family’s choice will trump current top-down federal programs if Congress will also forge a partnership with states to ensure that parents have the information to shop wisely for childcare, that childcare providers that can do harm to children are removed from the marketplace, and that center-based providers have incentives to evaluate their childcare staff and encourage the retention of the best.

Thank you for the opportunity to present this testimony.

Appendix

The Early Learning Family grant (ELF)

The early learning family grant (ELF) is conceptualized along the lines of the federal Pell grant system, which supports the college tuition costs of low-income students. Like Pell grants, ELF grants would go to parents if the form of a means-tested voucher that the family carries with them to the state-licensed childcare provider of their choice. That is very different from the present system in which federal dollars flow directly to Head Start and to states.

The amount of the voucher would be tied to the regional costs of childcare services, differentiated by type of provider (e.g., relative vs. center-based care, infant and toddler care vs. care for older children), duration in terms of hours a week, and topped up for children with disabilities that require extra staffing at the center level. The base voucher amount should be at the 75th percentile of the regional cost of services, as is currently the recommendation to states under the CCDBG, in order to ensure that low-income parents are not forced to buy childcare on the cheap.

Eligibility for an ELF grant would be made on the basis of family income in the tax return from the year prior to the uptake of the grant. Families with children under 5 years of age with income eligibility for an ELF grant would be informed of such eligibility at the time they submit their tax return. Families could also demonstrate through an application to a state-approved agent that they are currently eligible for an ELF grant when the evidence from the past year’s tax return is misleading or missing.

Families would be held harmless for increases in their income up to, say, 125% of the eligibility level in the year of uptake of the grant. For income increases beyond 125% of the eligibility level, families would incur a tax liability. These are but illustrations of important design decisions that would need to be made with respect to eligibility requirements so as not to provide an incentive for single parenthood or unemployment, and so as not to disrupt childcare placements based on short term changes in family finances.

The federal government would separately fund states based on a formula tied to a measure of child poverty, such as amount of their Title I funding, to create the oversight and information systems that eliminate the providers with unacceptably low quality, that encourage the growth of stronger providers at the expense of weaker providers, and that incentivize center-based providers to engage in consequential evaluation of the on-the-job performance.

States would be free to use their own tax resources to support additional childcare services. For example, they might increase the voucher level for poor families, serve as a direct provider of services, support universal programs, and provide home-based parental support services.

Congress would also fund research and development programs intended to identify tools and approaches that states could use to reliably identify differences in center quality and to nudge parents to utilize the information that states collect on center quality in their choice process. Likewise Congress would fund research to identify approaches and instruments that center-based care providers could deploy to evaluate the classroom performance of childcare staff.

The ELF program would designed to be budget neutral by setting initial parameters of the program such as income-eligibility and grant levels such that they would fall within the $12 – $20 billion that would be redirected from Head Start, the CCDBG, and other present federal early learning and childcare programs. This would be a discretionary program with Congress expected to adjust budget levels in future years based on experience with program utilization. Uncertainty over funding is not a desirable feature of childcare for parents, providers, or states. For that reason, Congress should pass a multi-year appropriation as soon as enough experience with the program is in hand to allow for reliable estimates of utilization.

[i] https://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2010/10/13%20investing%20in%

20young%20children%20haskins/1013_investing_in_young_children_haskins.pdf

[ii] http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1076.html

[iii] https://www.brookings.edu/blogs/brown-center-chalkboard/posts/2013/05/08-obama-prek-

budget-herbst

[iv] http://www.sciencemag.org/content/320/5884/1723.full?ijkey=9fON.EIKV6mQA&keytype=ref&siteid=sci

[v] http://www-siepr.stanford.edu/Papers/pdf/08-05.pdf

[vi] https://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/2013b%20cascio%

20preschool%20education.pdf

[vii] Anderson, Michael L. 2008. “Multiple Inference and Gender Differences in the Effects of Early Intervention: A Reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103, no. 484: 1481-1495. (See http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3982/QE8/pdf for a rejoinder to Anderson.)

[viii] https://www.brookings.edu/blogs/brown-center-chalkboard/posts/2013/05/08-obama-prek-

budget-herbst

[ix] https://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/2013b%20cascio%

20preschool%20education.pdf

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).